Reject and Inject

The Ethics of Cosmetic Procedures

If you’d like to listen this essay, you can find the audio version at the Brave New Us podcast entitled “Reject and Inject: Why Cosmetic Procedures Aren’t Just Skin Deep.”

I’ll never forget Katie’s cute button nose.

I met Katie1 while chaperoning a high school retreat. At age 17, Katie was a classic Snow White beauty with long dark hair, ivory skin, and rosy cheeks. As the retreat reached its crescendo on the third night, the teens’ masks began to fall away. Secrets dripped out, revealing their unfiltered hearts.

Katie’s rosy cheeks were wet with tears as she described an abusive boyfriend whose derisive mocking of her appearance had her deeply convinced of her own ugliness. Despite having escaped that toxic relationship years earlier, Katie remained haunted by this memory; each time she looked in the mirror, she saw the wounds he’d inflicted on the inside looking back her.

“My nose is perfect now,” she confessed, “But it isn’t mine.”

At age 14, before Katie had even finished puberty, her parents had funded the nose job she’d insisted she needed to be happy.

Though I wasn’t yet a mother at the time, my heart ached for Katie. Now that I am a mother, molten fury erupts in true mama bear fashion when I recall Katie cupping her hand over her “perfect nose,” as her tear-stained face reflected the broken heart inside her chest.

How could her parents allow her to get such a procedure, and at such a young age—much less fund it? Why didn’t they respond by telling her how beautiful she was, just as she was? Instead, they chose to subject her to serious medical risks, all the while confirming her deep fears that she was ugly, unworthy, and unlovable.

It’s easy to conjure this righteous anger on Katie’s behalf, but if we’re honest, don’t we all have a bit of Katie’s parents lurking inside us?

Maybe this isn’t what we’d say or do to our girls, but what about the girl we see in the mirror?

Reject and Inject: How the Beauty Industry Problematizes the Body

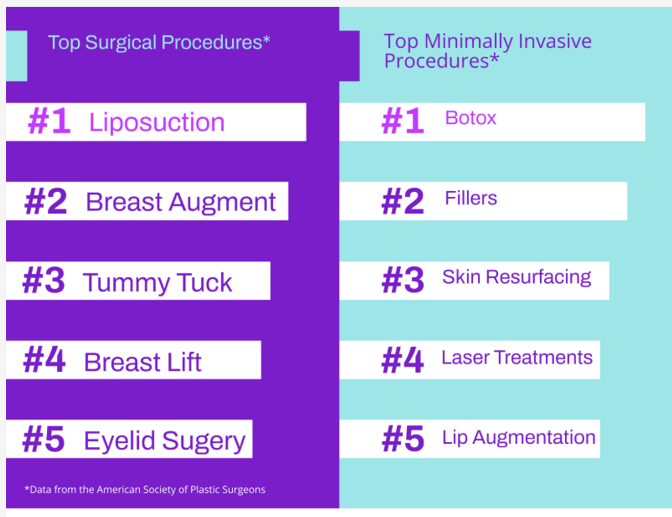

The beauty and cosmetic surgery industry is now a multi-billion dollar industry, with the United States leading the charge. Projections anticipate huge growth in this sector, from $61 billion to $83 billion in less than 10 years. Americans are lining up by the millions to get their tummies tucked, breasts augmented, noses tweaked, faces filled, and wrinkles flattened.

These procedures are not without serious risks. Aside from the standard risks of surgery, cosmetic procedures risk additional complications like breast implant illness and autoimmune disease. Even the cosmetics we use on a daily basis are known endocrine disruptors and carcinogens. These everyday cosmetic products expose users to thousands of synthetic chemicals, many of which are associated with reproductive disorders, diabetes, immune dysfunction, and cancers—chemicals that end up coursing through our bloodstreams.

Those are just the known risks for legitimate procedures. The loosely-regulated MedSpa industry is notorious for selling fraudulent and harmful treatments sourced from dubious sellers on sites like Ali Baba.

Despite the risks, the beauty industry is booming. What is fueling this growth? Does all this alteration actually make us more confident? Of course not. Women report skyrocketing rates of insecurity; it appears that the existence of cosmetic “solutions” serves not to quell women’s anxieties, but to exacerbate them.

This is not a conspiracy; it’s just good business. The industry telling us what we “need” profits most not by solving problems, but by creating them. The driving force behind the beauty industry is not to care for our bodies, but to problematize them. The more problematic our bodies become, the more solutions they can sell. For the beauty industry, the central question is not “how many steps does a skincare routine need,” but rather, “how many steps can we convince the customer to buy?”

This is the legacy we are passing on to our girls.

Today’s generation is not just facing unrealistic images distorted by photoshop anymore; social media filters show them in real time just how much “prettier” they could be—if only they fixed themselves. So-called “Sephora kids” spend hours browsing the makeup aisle and demonstrating multi-step skincare regimens valued in the $100s online. These regimens purport to fix problems girls this age don’t yet have. Meanwhile, these products are actively damaging their delicate skin barriers.

These Sephora girls grow into the 18-year-olds shelling out up to $1000 per session of “baby Botox”—preventative neurotoxin injections that allegedly keep wrinkles at bay (at the cost of muscle atrophy, flu-like aches, headache, nausea, and even bladder control problems). These risks they endure, despite evidence that the so-called “preventative” procedures seem to inadvertently lead to premature aging.

In a culture that normalizes medical means for nonmedical problems, where do we draw the line? Where is the boundary we ought not cross in pursuit of “beauty” (if you can even call it that)?

Just how much risk and pain and financial cost is ethically justifiable?

When it comes to medical procedures, we can distinguish between therapy (procedures intended to restore function and that aim at healing) and enhancement (manipulation of the body that doesn’t serve the ends of health). For example, a woman who undergoes a double mastectomy after a breast cancer diagnosis may receive breast implants to restore her figure. A burn victim may have plastic surgery to correct and restore appearance (think Jay Leno). These are medically similar but ethically distinct procedures from a cosmetic breast implantation or a face lift that freezes an actor’s face to iron out the wrinkles typical of old age.

Thanks to Pope St. John Paul II’s theology of the body, we know that the body speaks a language; what we do with our body communicates deep truths about reality. What are we saying when we cut and paste the flesh?

When we cut open healthy bodies and rearrange ourselves, we say something about the gift of the body. When we reject what we’ve been given simply because it isn’t to our satisfaction, we miss the mark. We fail to properly receive the gift of our self, our body, with gratitude.

God, our Father, declares us beautiful and worthy. Meanwhile, we open our wallets and shell out the money to reconstruct His handiwork.

“No, thank you,” we say, as we attempt exchange His gift for one of our own making.

And yet, this desire doesn’t arise from vanity alone. It comes from the same tender place as Katie’s tears—a longing to be loved, to be chosen, to be enough.

Wanting relief from that ache doesn’t make us shallow; it makes us human.

Okay. Fine. But what if I still kinda want the Botox?

One might argue that injections, as risky as they may be, are not rejecting God’s gift, but an attempt to preserve it, akin to washing a car, waxing wood floors, or darning a sock.

That view ultimately betrays a limited view of beauty, a worldly one rather than a heavenly vision. When we attempt to equate beauty with youth, we miss the gift of aging and allow a lesser end to eclipse our ultimate good. As Helen Roy writes:

Motherhood only “ruins the body” if you accept all of the priors of a regime premised on total sexual objectification. If we instead choose to conform our minds to the divine imagination, and to regard our bodies as the form of our souls, then motherhood actually does the exact opposite. Motherhood and every scar it leaves behind represents the generative expansiveness of love itself—and our proximity to the Creator as women.

We need not be mothers to see the “generative expansiveness of love” that is made possible by our bodies. As Servant of God Chiara Corbella Petrillo (our youngest’s namesake) expresses it:

The goal of our life is to love and to be loved, always ready to learn how to love the others as only God can teach you. Love consumes you, but it is beautiful to die consumed, exactly like a candle that goes out only when it has reached its goal.

We are all melting candles, giving light to the world by the slow dripping of our love.

We could remain solid and stiff—but what good is smooth wax that never shares its light with the world?

The smooth skin of our youth is good, and is only natural to want to hold on to what is good. The problem arises when we grip so tightly to lesser good that we have no room for the greater goods God is preparing us to receive.

When we try to freeze our faces, we place disproportionate importance on appearance, lending our limited energy to a project that is less worthwhile—and ultimately more futile—than cultivating the virtues of self-donating love.

When we see ourselves with Heaven’s eyes, our laugh lines become marks of joy, and wrinkles are wisdom etched on our faces. Aging is also a gift of humility—should we choose to accept it. As we watch our beauty fade, we become more free to memento mori, to practice remembrance of our finitude, and to occupy our hearts and minds with higher things. We might not know exactly how much time we have left, but we know for sure that it doesn’t increase as our birthday candles do.

As our beauty fades, we become like a flower. Having bloomed brightly and offered its sweet scent, it droops, dropping petals one by one until finally, its true gift is revealed: the seeds of the next generation. A single lily produces thousands of seeds.

This can be us, if we live rightly. We could dye our petals back, inject them with hydrating serums, or paste them back onto the stems. Or we can embrace our God-given limits, like the flower that blooms wide and produces abundant life—through its very diminishment.

So too does our love only come to full fruition when we offer ourselves generatively to others. The quintessential example of this is St. Teresa of Calcutta. I certainly can’t think of anyone else whose countenance was at once more wrinkly or more beautiful.

Of course it is natural to want to preserve the beauty God has given us (and perhaps it is comforting to know that this desire will be realized in the perfection of the resurrected body). Problems arise when we cling to our earthly beauty so tightly that we are willing to sacrifice inordinate sums, subject ourselves to serious risks, and reject the gift of the way we’ve been formed. When we grasp at a beauty we are sure to lose, we forget to strive for the beauty that lasts forever.

So when that twinge starts to unsettle us, let us quell those rising criticisms and, instead, treat ourselves the way Katie’s parents should have treated her.

After all, we are—each of us—God’s little girls.

If you’d like to continue these reflections, you can subscribe below. And if someone you love is wrestling with these questions, sharing this essay may be the gift they need.

Katie’s name has been changed to protect her privacy.

"We are all melting candles, giving light to the world by the slow dripping of our love.

We could remain solid and stiff—but what good is smooth wax that never shares its light with the world?"

What an absolutely beautiful reflection. I love candles so I will think on that image often.

Thank you, as always, for writing such a through reflection and bringing your expertise of ethics into it.

I remember a couple of years ago when I regularly listened to Alex Clark's podcast she said something along the lines of men who claimed they wanted natural looking women being delusional because all of the natural beauty women actually had botox or lip filler. It has never crossed my mind to get a needle stuck in my face, even having dealt with deep insecurities about aspects of my body. I was flabbergasted how she saw that as completely status quo to pay for something like injections.

The women I have loved and revered most in this world have all had deep wrinkles, white hair, sagging breasts and a pooch on their lower stomachs. I can't say for certain that they loved how they looked but they were lively and gave of themselves fully. I hope women still get to experience elders like that as the trends of cosmetic surgery increase.

I am reminded of one of my favorite lines by Whitman: "and your very flesh shall become a great poem." Hopefully as our generation of women age we are able to become epic poems and drip out our burning love as God created us.

This is such a beautiful reflection. I often think about how the standards of the early 2000’s impacted me growing up. It was all super unrealistic skinny celebrities and low rise jeans. I didn’t think it impacted me at the time, but I do see now how it shaped how I see things and even see myself. It’s taken a lot of work to do what you suggest in this piece—to see myself through God’s eyes, especially in my body after multiple children. Thank you for the reminder!